“Beards for the Boys” Cancer Awareness Campaign

Have you been looking for a good excuse to grow your beard? You just found one!

3 min read

Cancer Support Community

Mar 24, 2023 3:20:22 PM

Cancer Support Community

Mar 24, 2023 3:20:22 PM

When it comes to self-advocacy, we talk a good game. We tell patients to ask questions, to seek clarification when they don’t understand the answers and to make sure their values and goals are part of the discussion. We urge people facing cancer to take an active, educated role in their treatment decision-making, to seek second opinions. When communications between doctors and patients break down, we encourage patients to find new care providers. It’s easier said than done.

For a significant percentage of people facing cancer, or any serious disease, becoming an effective self-advocate poses a range of challenges. Becoming a cancer patient means entering a new world, one in which patients and their caregivers confront an increasingly complex array of treatment options. At a time when individuals are dealing with fear, uncertainty and disruptions in every key aspect of their lives, we expect them to educate themselves and make informed decisions about issues with which they have little or no experience. In many instances, this also means shifting the paradigm of doctor-patient communications from the more traditional one-way physician-tells-patient-what-to-do to a two-way, interactive discussion between equals.

My own situation is one example of how difficult this process can be—even for someone who has spent her life in the oncology world researching patient behavior and advocating for more effective doctor-patient communications. After my second cancer diagnosis, breast cancer, I underwent a course of chemotherapy that resulted in numbness and tingling in my feet, known as neuropathy. I have an excellent doctor, but it was not until I had fallen several times that I asked for a referral to a physical therapist, and I actually felt guilty about “bothering” my very busy physician with an issue that was seriously compromising my life. And then, it took some time until I scheduled the appointment. Somehow the fact that I asked for the referral meant that it must not have been a priority. The upside of my advocating for myself is that I truly benefited from getting the physical therapy that I needed, and I haven’t fallen since.

We hear about these issues all the time, both in the data we collect through our Cancer Experience Registry and the personal accounts of the patients and caregivers who participate in Cancer Support Community programs. On the anecdotal level, I think about a young African-American woman from Texas who sobbed as she described her frustration with her doctor’s unwillingness to answer her questions about her cancer. She had tried writing her questions down, bringing someone with her to her appointments, reading about her condition, but her efforts to communicate were brushed off. She couldn’t even get an answer as to the stage of her cancer. The result was frustration, fear and high levels of anxiety about her future. For this woman, effective self-advocacy meant changing doctors, but she was afraid to make that move, to leave her small town for a treatment center in a more distant city.

.jpg?width=392&name=shutterstock_71731051%20(1).jpg)

Our data bear out these concerns. While most patients report receiving information about their treatment options, less than half report being knowledgeable about their treatment options, and a significant proportion reported not having enough knowledge or support to fully engage in treatment decisions. Over half felt significantly unprepared to discuss treatment options with their doctor. We have also learned that it is not uncommon for patients not to report all of their symptoms and side-effects from treatment to the healthcare team. Among survivors of multiple myeloma, a rare blood cancer, over one-third (36%) did not report all symptoms and adverse effects to their doctors or nurses. The most common reason was, “I don’t think anything can be done about these problems.”

The bottom line is that it is not enough just to tell patients and caregivers that they need to be self-advocates. To empower patients, we need to provide individuals facing serious diseases with the resources and the skills to make this possible. That means ensuring that patients have accurate information that they are able to understand and use, assisting them in developing appropriate questions, making it easy to access their medical records, and opening the doors to thinking about what is important to them at various decision points during the course of treatment.

Patients can learn skills to help them communicate better, use their time and that of their doctors’ wisely, know when to ask for additional help. One doctor with whom I have worked suggests that patients who have complicated issues to discuss notify the office in advance so that the extra time can be made available. Patients also benefit from taking advantage of the patient-centered care that nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers and patient navigators offer. When, for whatever reason, the relationship isn’t working, patients need the skills and confidence to make changes.

In addition to discovering or acquiring the skills needed to become effective self-advocates, people facing cancer also need to be empowered to believe that their voices can and should be heard. Older people, those who are less educated or come from lower socioeconomic groups—those who are timid by nature—may find it difficult to question someone they perceive as authority figures who control their destiny. They may fear asking “dumb” questions or alienating their doctors by questioning them. And, trust is critical to any good doctor-patient relationship. Patients want to believe in their doctors. The goal must be to create a safe, secure and nurturing environment which encourages every patient and caregiver to trust not only their treatment teams but also to ask for what they need.

Joanne Buzaglo, Ph.D.

Senior Vice President of Research & Training

Cancer Support Community

Have you been looking for a good excuse to grow your beard? You just found one!

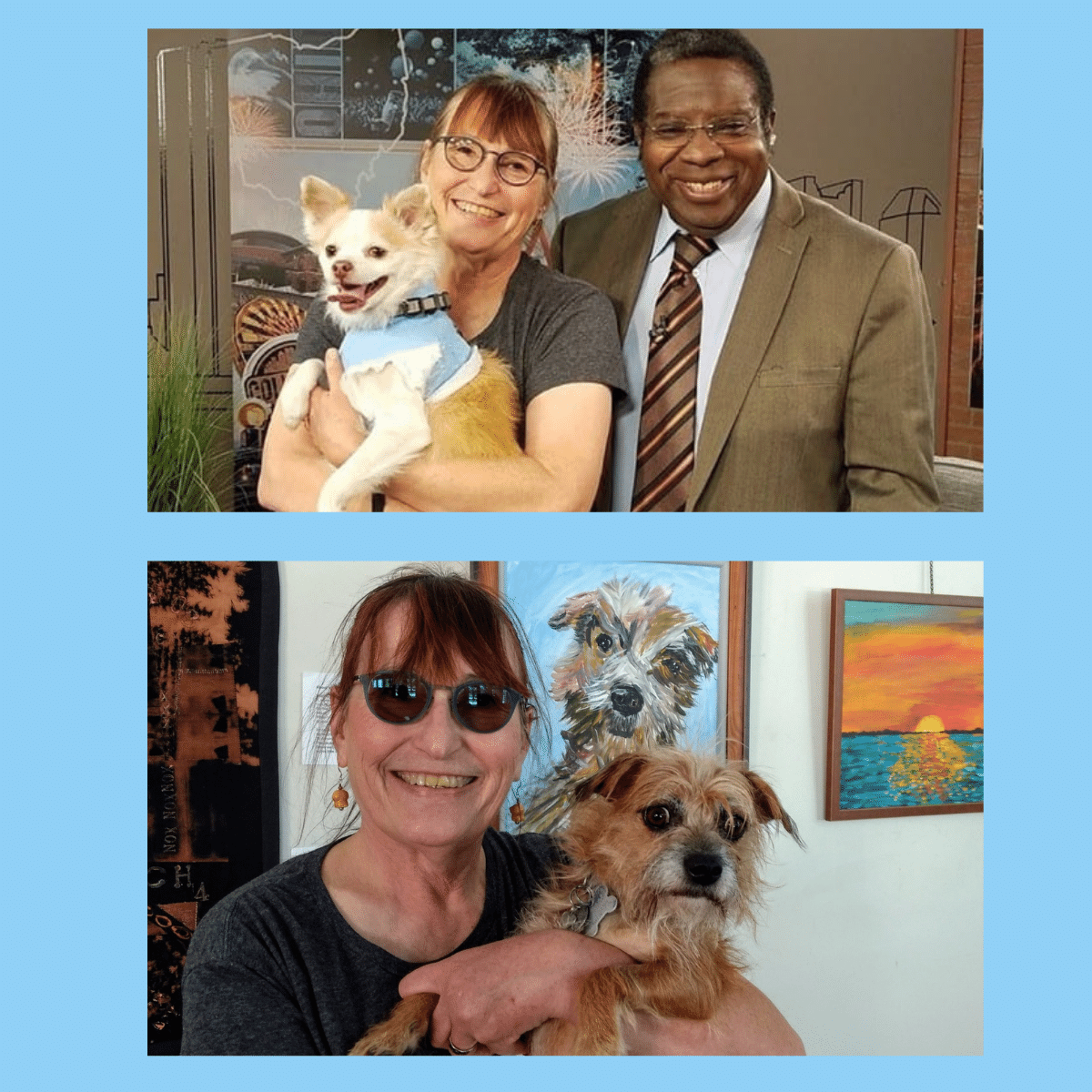

The following is an interview a member of our staff conducted with participant Nancy Fritz! We’re excited to share her story and hope she inspires...

Portia was diagnosed with breast cancer in January 2019. She credits regular mammograms for early detection. After her diagnosis, Portia had...